The Makings of a Public Goods Campaign

Many of the resources and services upon which our lives depend are in private hands, bought or sold in the market for profit. A public goods campaign aims to change that by moving resources or power in the direction of public or community control and benefit, and away from private control and profit. A public goods campaign meets four principles, with a racial justice lens and commitment to antiracism running through each:

- Uses framing that shows the benefit for a broad public or an expansive constituency

- Points to root causes (such as the profit motive), not just symptoms

- Builds a bigger we, bringing more people and constituencies into the struggle by redrawing the lines of who wins, who loses, and who sees themselves in the solution

- Shifts power and resources from private profit to public control

Voting Restoration in Virginia

Virginia Organizing

Virginia Organizing (South Hampton Roads)

The Victory

In 2016, after years of grassroots pressure, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe signed an executive action restoring the voting rights of 206,000 returning citizens, then restored these rights individually when the executive action was declared unconstitutional. Virginia Organizing and allies continue to fight for a change in the state constitution to preserve their win.

The Campaign in Virginia

Since 1998, Virginia Organizing has been fighting for automatic restoration and an end to the opaque, tedious process of requesting restoration directly from the governor. As part of the campaign, Virginia Organizing helped members complete the restoration process, often combining this help with base-building and public education — for instance, at events where organizers generated calls and letters to the governor while assisting people with applications.

Virginia Organizing approached voting rights as part of a larger campaign for the rights of returning citizens. The organization led a “ban the box” effort to protect returning citizens when they applied for jobs. In Lynchburg, they successfully defended the right of parents and other family members to enter their children’s public schools. Across these efforts, Virginia Organizing developed relationships with teachers, business owners, city officials, church leaders, and impacted families around that state. Virginia Organizing mobilized these supporters and its base of returning citizens when McAuliffe was elected in 2014 and kept the pressure on.

How Applying Public Goods Principles Strengthened the Fight

- When putting families, colleagues, and directly impacted folks in front of representatives and law-makers, Virginia Organizing brought attention to the community-wide impact of restoring rights to returning citizens.

- During the campaign to restore rights, Virginia Organizing pointed to the systemic cause of the problem: the fact that Virginia’s failure to automatically restore people’s voting rights after they complete supervision is a legacy of Jim Crow, deliberate suppression of the votes of people of color, and an example of institutional racism.

- In local chapters and as a whole, Virginia Organizing engaged a diverse group of community members and organizers, including returning citizens looking for rights, engaged family and friends, as well as employers and neighbors inspired by the fight. Each member of the campaign understood the injustice of this widespread disenfranchisement in their state.

After the Governor’s executive order, Virginia Organizing got the process streamlined to a one-page online application that’s always approved as long as a person meets the criteria. Each Virginia Organizing chapter also does rights restoration work with members, including holding widely-attended know-your-rights events. This victory has created a shift in the balance of power, creating a larger and more equitable voting public, and Virginia Organizing is optimistic about winning a constitutional amendment for automatic restoration in the near future.

Housing Justice for All in New York State

Citizen Action of New York & the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance

The Victory

In 2019, New York passed a suite of housing justice laws lifting the state ban on rent stabilization, limiting add-on charges for improvements, creating new protections for renters in manufactured home communities, and more. The victory reflects the Housing Justice for All campaign’s statewide consolidation of the power of tenants, unhoused people, and public housing residents. A member of the coordinating committee of the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance (which leads Housing Justice for All), Citizen Action of New York (CANY) brought in a statewide organizer and leveraged its geographic reach from Buffalo to Binghamton.

The Campaign in New York

In 2018, Democrats took control of the state House and Senate, and housing justice groups saw an opening. But the real estate industry has poured millions into state politics, and CANY and its partners in Housing Justice for All and the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance knew they’d need a show of force in all corners of the state. This required crafting legislation with both broad and targeted appeal. The result was a nine-bill package framed as universal rent control — a package a broad statewide coalition could unite around and fight for in the face of attempts to peel groups away. For instance, immigrant-led organizations in New York City emphasized limits on add-on charges (a rent control loophole), while removing the ban on rent stabilization was a priority for groups beyond the New York City region.

The campaign applied constant pressure with twice-a-week lobby days and escalating tactics that kept the opposition on its toes. The power of escalation became clear in a pivotal mass day of action, when 3,000 people occupied the state capitol, declaring their unity by chanting “all nine bills.” Ten days later, Governor Cuomo signed legislation including eight of those laws.

How Applying Public Goods Principles Strengthened the Fight

- Under the “universal rent control” banner, CANY and other Housing Justice for All partners made clear that tenant protections bring stability to New Yorkers in cities, suburbs, and towns, in apartment buildings and mobile home courts. The campaign also presented the lifting of rent stabilization preemption as an important option for local governments to protect their communities from housing shortages.

- The campaign was explicit about the root cause of the crisis, identifying corporate domination of housing as the culprit. The campaign also framed housing as a human right, something that should not be sold for profit. Instead, the coalition described housing as something that should be guaranteed to everyone.

- Formation of the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance in 2017 was crucial for the 2019 win. Previously, housing reform had been blocked as a downstate issue. The coalition aligned geographically dispersed groups with different sets of interests around a package that expanded the constituency for reform

- The coalition achieved the largest win in decades, granting millions of New Yorkers increased tenant protections. Affirming public limits on extraction through rent, the victory was hailed as a “seismic shift” in the relationship between tenants and landlords and in the balance of power in Albany.

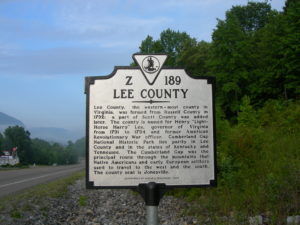

Pushing Medicaid Over the Line in Lee County

Virginia Organizing

The Victory

In 2018, Virginia passed Medicaid expansion after years of deadlock, bringing health care to 450,000 Virginians. A 110-organization coalition, Healthcare for All Virginians, won the fight with a broad, multiracial constituency that made the case for health care as a public good. Virginia Organizing, a core coalition member, organized in pivotal parts of the state where other groups weren’t organizing, such as the Southside, Southwest, and Shenandoah Valley.

The Campaign in Lee County

Virginia Organizing’s chapter in Lee County led the fight in Southwest Virginia, once home to a hugely profitable coal industry. The county is represented by Republican Delegate Terry Kilgore, then chair of the Commerce and Labor Committee, the number three spot in House leadership.

In 2013, the Lee County hospital was closed by its private purchaser, citing the state’s refusal to expand Medicaid. Virginia Organizing led the fight to reopen the hospital — bringing in nurses, ambulance drivers, local elected officials, and others — and leveraged the hospital fight publicly in its Medicaid campaign. The hospital fight put Virginia Organizing members in consistent contact with Kilgore to make the case for Medicaid. After the 2017 election, Kilgore came out for Medicaid, and 17 Republican delegates went with him, including delegates in the Southside and Southwest, where Virginia Organizing was active. This broke the legislative logjam.

How Applying Public Goods Principles Strengthened the Fight

- Centering the local Medicaid fight on the loss of the hospital, Virginia Organizing showed the community-wide stakes. This underscored how much Medicaid mattered to people’s health and safety, as well as jobs and resources in the community.

- While fighting to reopen the Lee County hospital, Virginia Organizing consistently pointed to a larger, systemic cause of the loss: state lawmakers’s refusal to dedicate resources to Virginians’ health care, letting people get sick rather than expanding Medicaid.

- In Lee County and around the state, Virginia Organizing knitted together a multiracial, varied constituency for Medicaid — not just Virginia Organizing members across race who needed health care, but also nurses who’d lost their jobs, local elected officials, Black churches and other faith leaders, health care providers, and addiction recovery professionals.

- Thanks to the win, 450,000 more Virginians now get health care through a public program, shifting health care toward public control.

Manufactured Homes Residents Go Up Against Private Equity

MHAction

The Victory

In November 2020, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) announced new requirements on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s manufactured home community lending, responding to your calls for reform. Under the new rules, half of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s multi-family loans must go to affordable housing, and to be considered affordable manufactured home communities must be resident-owned-cooperatives, non-profit-owned, or commit to FHFA’s tenant protections. This step in the right direction is a win for MHAction, which is crafting and winning a range of solutions for manufactured home residents seeking to wrest control of their communities back from private equity landlords.

Connecting Manufactured Housing Community Residents around the Country

Manufactured home communities are one of the largest sources of affordable housing, especially in rural and exurban locales. With family ownership of manufactured home communities on the decline, private equity is swooping in. These firms are amassing mobile home community portfolios and siphoning wealth from residents as they do with hospitals, retailers, and other sectors. This means skyrocketing rent paired with neglect on upkeep and maintenance for residents who have title to their non-mobile, manufactured homes but not the land beneath them.

MHAction is building a nationwide, multiracial, primarily women-led base of manufactured home residents in rural and exurban communities in states like Iowa, Florida, Michigan, North Dakota, and elsewhere. Using online and offline organizing (including targeted Facebook ads), MHAction connects people across state lines around shared experiences, often with the same predatory private equity firm, in addition to working deeply in specific communities. The organization’s goal is to unite residents around not just their common interests but also around their shared identity. In this way, they build the foundation for residents to fight for collective solutions for their manufactured home communities (whether in the form of a land trust, cooperative or nonprofit ownership, or state regulation). This style of engagement also allows MHAction to lend its unique voice to broader social, economic, and racial justice issues that range from caregiving to climate change.

How MHAction Is Applying Public Goods Principles

- MHAction grounds its work in the broad value that every family deserves a place to call home. Also, by bringing manufactured home residents into larger fights for tenants’ rights and stable homes, MHAction helps show the broad interests in housing justice across rural, exurban, and urban geographies.

- With its focus on private equity, MHAction draws attention to the contradictions that underlie mobile home communities—the exploitation of the idea of ownership, the corporate owners’ extreme profit-driven business model, and the false idea of mobility when residents are all but trapped.

- Connecting people digitally in far-flung communities, MHAction is doing deliberate work to build relationships and analysis across race, carrying out deep conversations and political education on anti-Black racism, immigrant justice, and more. The aim is to help people find what binds them together as neighbors and manufactured home residents committed to shared values, a sense of community, and hope for justice.

- MHAction wins a range of public goods alternatives to private or profit-driven corporate ownership—all ways of shifting ownership and calling into question corporate control of the land beneath people’s homes.

Our Colleges, Our Future

Communities for Our Colleges

Washington state’s community and technical colleges educate 360,000 students a year, nearly half students of color. Yet, even before Covid, the colleges persisted on shoestring budgets, underpaying contingent faculty, overworking staff, and skimping on counseling, advising, and wraparound services for students. When the pandemic hit, lawmakers started talking about slashing funds even more. Communities for Our Colleges pivoted to online organizing and strategies for shifting the conversation away from cuts and toward investment.

Building a Broad Constituency for Community Colleges

The campaign used online outreach to build a team of student leaders from both sides of the Cascades, an important political divide in the state. The campaign then created a fellowship program to lead base-building and drafting of a report sharing students’ recommendations for specific investments. Throughout, the campaign has cultivated relationships with faculty and staff unions (particularly adjuncts), alumni, families, and college presidents. The power of this constellation became clear when the campaign held a first-of-its-kind statewide organizing meeting co-led by students and faculty. In the run-up to the legislative session, Communities for Our Colleges is bringing this broad constituency into conversation with lawmakers, making the case for an investment in community and technical colleges as core institutions that must reflect the values, priorities, and standards of their communities.

Applying a Public Good Framework

- The campaign draws a picture of community colleges’ potential as generators of knowledge, economic equity, and full social and civic participation for different groups across the state — first-generation students, immigrant families, college staff, older students, Black and brown families, and local businesses.

- As the campaign makes clear, the disinvestment in community and technical colleges reflects the growing corporate orientation of public higher education, treating students as consumers, putting the squeeze on faculty and workers, and compounding structural racism.

- Communities for Our Colleges is putting students at the front of a broader campaign that includes faculty, staff, alumni, administrators, and more.

- Communities for Our Colleges is pushing back against the idea that diversity and inclusion alone will equal racial equity. The campaign is calling for full investment to fund comprehensive financial support and wraparound services for students and job quality for faculty and staff.